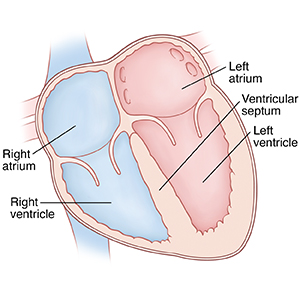

When Your Child Has a Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)

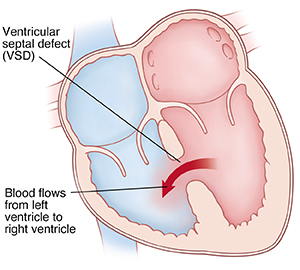

The heart has 4 chambers. A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a hole in the dividing wall (ventricular septum) between the 2 lower chambers (ventricles) of the heart. A VSD can occur anywhere in the ventricular septum. Left untreated, this defect can lead to certain heart and lung problems over time. But the problem can be treated.

|

| Normal heart. |

|

| A VSD causes blood to flow from the left to right ventricle. |

What causes a ventricular septal defect?

A VSD is a congenital heart defect. This means it’s a problem with the heart’s structure that your child was born with. It can be the only defect. Or it can be part of a more complex set of defects. The exact cause is unknown. But most cases seem to occur by chance. Having a family history of heart defects can be a risk factor.

Why is a ventricular septal defect a problem?

Blood normally flows from chamber to chamber in 1 direction through the left and right sides of the heart. With a VSD, blood flows through the defect from the left ventricle to the right ventricle. This is called a left-to-right shunt. It causes more blood than normal to pass through the right side of the heart and lungs. It causes the left side of the heart to become enlarged (dilated). More blood than normal has to be pumped to the lungs. With a large VSD, the lungs can become filled with extra blood and fluid. When this happens, your child develops a condition called congestive heart failure (CHF). In the case of a large VSD, the extra blood flow can increase the pressure in the pulmonary arteries. These are the blood vessels leading from the heart to the lungs. Over time, this can cause more lung problems.

What are the symptoms of a ventricular septal defect?

A child with a small or medium-sized VSD may have no symptoms. A child with a large VSD can develop CHF and will have symptoms. These can include:

-

Tiredness

-

Trouble breathing or rapid breathing

-

Trouble feeding (in babies)

-

Poor weight gain and growth (in babies)

-

Fast heart rate

-

Enlarged liver

-

Pale skin color

How is a ventricular septal defect diagnosed?

During a physical exam, the healthcare provider checks your child for signs of a heart problem, such as a heart murmur. This is an extra noise caused when blood doesn’t flow smoothly through the heart. If a heart problem is suspected, your child will be referred to a pediatric cardiologist. This is a healthcare provider who diagnoses and treats heart problems in children. To check for a VSD, these tests may be done:

-

Chest X-ray. X-rays are used to take a picture of the heart and lungs.

-

Electrocardiogram (ECG). The electrical activity of the heart is recorded.

-

Echocardiogram (echo). Sound waves (ultrasound) are used to create a picture of the heart and look for structural defects.

How is a ventricular septal defect treated?

If your child has CHF symptoms, medicines will be prescribed, most often a diuretic or "water pill." They can help reduce the amount of extra fluid in the lungs and ease the work of the heart.

Some VSDs may close on their own. So, the cardiologist may check your child’s heart regularly and wait to see if a VSD closes.

If a VSD is large, causes severe symptoms, or doesn’t close on its own, closure is needed. VSD closure is usually done with heart surgery.

Your child’s experience: heart surgery

Heart surgery to close a VSD is done by a pediatric heart surgeon. The surgery lasts at least 4 to 6 hours. It takes place in an operating room in a hospital. You’ll stay in the waiting room during your child’s surgery.

-

Before surgery. You’ll be told to keep your child from eating or drinking anything for a certain amount of time before surgery. Follow these instructions carefully.

-

During surgery. Your child is given medicines (sedative and anesthesia) to sleep and not feel pain during surgery. A breathing tube is placed in your child’s trachea (windpipe) during this time. Special equipment keeps track of your child’s heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen levels. Your child is also placed on a heart-lung bypass machine. This allows blood to continue flowing to the body while the heart is stopped so that it can be operated on. An incision (cut) is made in the chest through the sternum (breastbone) to access the heart. The VSD is closed with stitches or a patch, or both. Then your child is taken off the bypass machine and the chest is closed.

-

After surgery. Your child is taken to a critical care unit to be cared for and watched. Several catheters, tubes, or wires may be attached to your child. These are in place to assist the medical team in caring for your child. You can stay with your child during much of this time. They may remain in the hospital for 3 to 7 days. When your child is ready to leave the hospital, you’ll be given directions for home care and follow-up.

Risks and possible complications of heart surgery

Risks and possible complications may include:

-

Reaction to sedative or anesthesia

-

Incomplete closure of the VSD, needing more treatment

-

Arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm)

-

Infection

-

Bleeding

-

Nervous system problems, such as seizure or stroke

-

Abnormal buildup of fluid around the heart and lungs

-

Death

When to call the healthcare provider

After heart surgery, call the healthcare provider right away if any of the following occur:

-

Pain, swelling, redness, bleeding, warmth, or fluid leaking at the incision site that gets worse

-

A fever (ask the healthcare team what temperatures to be concerned about)

-

Fast or irregular breathing

-

Increased tiredness

-

Nausea or vomiting that doesn't go away

-

A cough that won’t go away

Call 911

Call 911 if any of the following occur:

What are the long-term concerns?

-

A VSD that’s left untreated can lead to more health problems later in life. Your child is more likely to have growth problems, frequent respiratory infections, and develop disease of the blood vessels in the lungs after a year of age. Your child's development will be watched closely.

-

After treatment, most children with a VSD can be active like other children.

-

Your child will need regular follow-up visits with the cardiologist. Your child will need less of these visits as they grow older.

-

Your child may need to take antibiotics before having any surgery or dental work for 6 months or longer after surgery. This is to prevent infection of the inside lining of the heart and valves. This infection is called infective endocarditis. Ask your child's cardiologist about this.